In 1975, Stanley Kubrick released one of his (relatively) lesser-known works, Barry Lyndon. Loosely based on the 1844 novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon by William Makepeace Thackeray, it takes place in the second half of the 18th century in England, Ireland, and Germany, following Irishman Redmond Barry through his long and complicated journey from a state of little opportunity and wealth to one of great riches and then back again.

While Barry Lyndon is often remembered by critics and film scholars for its gorgeous painting-like cinematography and Hogarth-inspired visuals, a major element of its success as a period piece and epic is its music. Kubrick always had a fondness for classical music. His 2001: A Space Odyssey is well-known for juxtaposing science fiction technology with classical compositions as well as its opening sequence set to Richard Strauss’ “Also sprach Zarathustra,” and A Clockwork Orange’s soundtrack primarily features electronic and synthetic renditions of Rossini and Beethoven. Barry Lyndon continues this trend, but its devices are more subtle.

It might seem odd to pick Barry Lyndon for analysis considering all of its Celtic music is contained within the first 45 minutes of this three-hour film, but what few Irish pieces the movie does contain are essential for its thematic underpinnings and the development of Redmond Barry’s character, especially his inability to ever settle down and his interminable condition as an outsider in all settings, names, and ranks he finds himself in.

After a brief prologue showing the duel that killed Barry’s father, the omniscient narrator of the film introduces us to Barry while he plays a card game with his older cousin Nora Brady, a young woman with whom he entertains an infatuation. She flirts with him, but it is apparent that he takes the coquetry much more seriously than she does. Kubrick’s work often has an odd sense of humor, and it is definitely not restrained in the opening moments of the film. Brady puts a ribbon in her cleavage while Barry looks away, and then challenges him to find it. What proceeds is one of the more awkward interactions in the film as Barry very slowly, nervously, unsuccessfully looks for the ribbon. Eventually, she reveals it to him, and they kiss. Scoring the whole sequence is The Chieftains with Seán Ó Riada’s classic "Mná na hÉireann” (“Women of Ireland”). Being one of the most famous recordings of the song, it was released two years before the release of Barry Lyndonon The Chieftains 4. It is solely an instrumental version with no vocals.

Although serving little narrative consequence in the long run, this early scene helps establish Barry as an immature, naive young man. It seems like the sort of scene you would see in any other period piece, but some of Kubrick’s creative decisions complicate things, especially his casting and of course his music selection. Ryan O’Neal plays Barry. Before ’75, he had already made quite a career for himself, having been in Love Story (for which he was nominated for an Oscar), What’s Up, Doc?, and Paper Moon. Although both of his parents had partial Irish heritage, neither ever lived there, and O’Neal was born and raised in Los Angeles. He was in his thirties when they shot Barry Lyndon.

From the very beginning, there is an undeniable dissonance between the various elements of the film. O’Neal feels out of place in almost every scene, from Barry’s beginnings in Ireland all the way to when he settles in England. In 2020, it is easy to lose a sense of how peculiar the casting was for this film in ’75 since now, because of Kubrick’s later success and Barry Lyndon’s critical reevaluation, we remember Barry as O’Neal, but at the time of the movie’s release, O’Neal was most famous for films like Love Story, a sappy romantic drama that was a huge box office hit ($136 million on a $2 million budget). He played an upper-class East Coast Harvard graduate, quite a distance away from a down-on-his-luck young Irishman.

After Barry and Brady’s kiss, the film hard cuts to a line of British infantry. The non-diegetic “Women of Ireland” is replaced with a diegetic rendition of “The British Grenadiers,” a traditional marching song often played by the British, Canadian, and Australian militaries. It is here where we begin to see how Kubrick assembled Barry Lyndon’s soundtrack in a way that highlights incongruity, otherness. Leading the march is wealthy British Army captain John Quin who, following the march, we see interacting with Brady. Later, it is then revealed that her family intends to marry her off to Quin for their financial benefit. Being only vaguely interested in Barry anyway, Brady quickly sides with her family, and she is soon engaged to Quin.

Barry first sees Brady and Quin together after the “The British Grenadiers” when the British military personnel begins to dance with the local Irish women. The sequence is set to the traditional song “Piper’s Maggot Jig” performed once again by The Chieftains. During this high-spirited jig played with a group of wind instruments and fiddles, we see two elements of interest. First, Quin’s dance—he seems to make an attempt at keeping up with the traditional dance, but he makes such large strides and moves so slowly that he looks ridiculous. At a certain point, he stops, out of breath, and just stares at Brady as she continues to dance. None of it accrues him sympathy, however, as he has a plain look of mockery on his face throughout the engagement, whether he intended to or not. Second, the Irish jig is played by the English military’s band. Of course in reality these men were not playing the music since, as said earlier, the piece was performed by The Chieftains, but the film makes it appear diegetic, cutting to the band in-between shots of the people dancing.

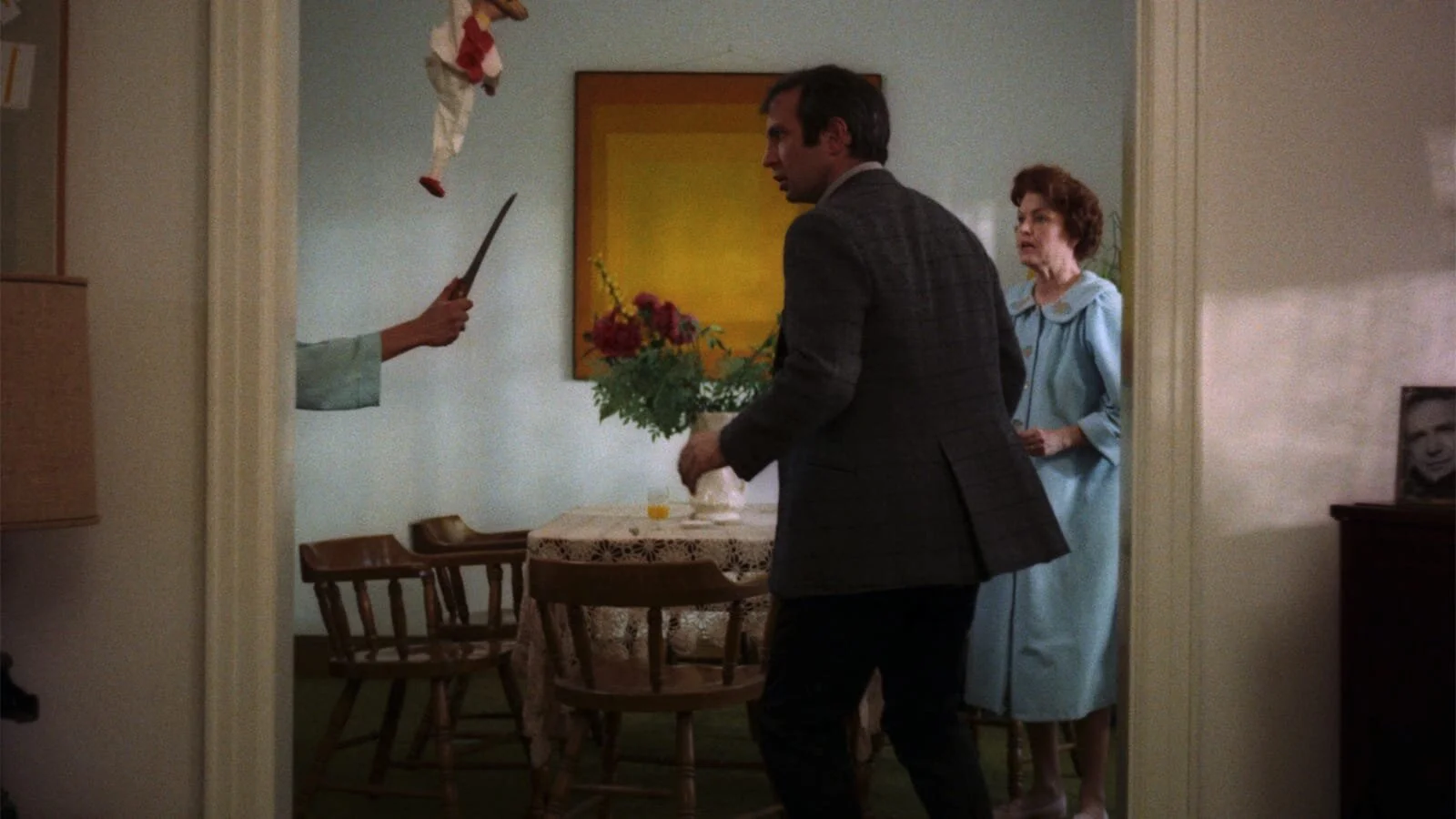

The next scene is between Quin and Brady as he courts her. During this interaction, Kubrick inserts a slightly different variation of “Women of Ireland.” The song continues as Barry learns of their engagement at dinner. Everything about these scenes is geared toward alienating Barry: the camera often lingers on his lonely close-up, the lighting separates him from everyone else, and the music of his homeland is used and abused by Englishmen (as one of them steps in and steals his love).

Barry has a violent confrontation with Quin and, as a result, has to leave Ireland to avoid the law. He is robbed at gunpoint as he exits town and is left to walk off without any belongings nor a horse—meanwhile, the last two pieces of Irish music in the film make their appearance. First, there is a sorrowful rendition of “The Sea-Maiden,” and then as Barry meets the thieves, we hear a very mysterious, unsettling version of Ó Riada’s “Tin Whistles.” Both were once again performed by The Chieftains.

Barry does not step foot in Ireland again until his fall from grace at the very end of the film. Upon his return (with only one leg and no money to his name), no Celtic music is heard. In a sense, after his confrontation with Quin and his ejection from Ireland, he had decided his homeland and its culture were dead to him. The rest of the film, replete with English and German classical compositions from the period, follows Barry as he tries to distance himself from his origins—he changes his name multiple times, joins both the British and Prussian armies, and, in what becomes his ultimate failing, he attempts to acquire a noble title. The portion of the film containing Celtic music is brief, but it serves an essential function of setting the stage for Barry’s struggle with identity. As Barry parades around like he is German, Prussian, English, we the audience know the truth about Barry. Having been estranged from his home at an early age, he is ceaselessly an outsider, physically and mentally, and something within him is incapable of finding true satisfaction wherever he goes.

While Kubrick heavily depended on classic Celtic compositions and the associations that the audience has with them, there is no reason to believe that Kubrick and the other creatives who worked on the film had any intention to belittle Ireland’s culture or mock its music, even if Barry and other characters within the film are dismissive of them. If one takes a look at how films with actual bigoted intent—or even films that unintentionally propagate bigoted or stereotypical views—went about depicting other cultures and minorities, then it becomes apparent that Barry Lyndon does not have this shortcoming. In “Music as Ethnic Marker in Film: The ‘Jewish’ Case,” Andrew P. Killick examines depictions of Jewish people in popular media. Some examples include explicit Jewish stereotypes, but the majority are more covert (with the typical stereotype being that of the “Shylock,” a Jew who is completely driven by profit). He does not “posit a deliberate conspiracy of anti-Semitic composers” but rather “that the use of this ‘Jewish music’ in association with lyrics expressing desire for money can help to reproduce and perpetuate a prejudice in the broader society without anyone’s having deliberately set out to do so” (Killick 187). The key here is the “Jewish music” Killick describes. In almost all cases, it is not actually Jewish music. Instead, it is an approximation of what (often American or British) composers think sounds like Jewish music to the general public. Fiddler on the Roof codified this sound which Killick categorizes into two groups: “the rustic dance and the synagogue chant” (189). Writers and composers would use this stereotypical Jewishness essentially as shorthand to communicate to the audience a character’s greediness and ugliness. Killick also examines the various adaptations of Oliver Twist over time, particularly how later versions hid its anti-semitism by taking the allusions out of the text and instead using the music to “furnish the principal clues” (193).

Unlike the examples Killick touches upon, Barry Lyndon relies upon already written music completely. There is no opportunity to caricature the Irish identity through music. Additionally, Barry Lyndon is not about the Irish or Celtic culture as a whole but rather Barry’s indefatigable struggle of identity within and without his Irish roots.

Martin MacLoone comes closer to finding trouble with Barry Lyndon’s depiction of Ireland in his book Irish Film: The Emergence of Contemporary Cinema. Although he mainly discusses the trend of depicting Ireland as either “bathed in romantic sensibility” or “torn asunder by violence and internecine strife” (34), he also passes “judgement on the ‘outsider’ tradition of representation” (33) that has also been present in much of cinema centered around the Irish. Indeed, Barry Lyndon is one of these films—Kubrick presents Barry as an “other”—but what confounds this argument is that Barry is a misfit in every environment. The Irish are not the “other” in Barry Lyndon; it is Barry himself. In fact, his “Irishness” has nothing to do with with his “otherness.” As we see later in the film, his failing as a British aristocrat and the breakdown of his family ultimately is due to his brash, selfish, inebriated ways, not his ethnicity.

Kubrick’s obsessive tendencies are well-documented and discussed, but often analysis of his films fall short of fully acknowledging the breadth of his craft (in addition to that of his numerous collaborators). In particular, with Barry Lyndon, the peculiar casting and the minimal but elegant Irish music selection interact in such a unique and metafictional way, all coming together for a single purpose: relating the life and times of foolish Redmond Barry, an eternal wanderer, a stranger to everyone.

Rewatch rating: 5/5